drink ya damn chicken soup, son

moving, J.D. Salinger, catching up with old friends, Heraclitus, Franny and Zooey, Wes Anderson

I’m in one of those period of life where I’m getting squeezed and stretched in every direction. Work is crazy. Moving houses. Baby on the way. Barely have time for friends or family, let alone myself.

It’s cool, though. I’m handling it. And one way I’m handling it is re-reading all these books that made me first fall in love with reading and writing. It feels like I’m catching up with old friends I haven’t spoken to in ages. And like what tends to happen in real life when catching up with an old friend (that is, if you were good friends and all), I’m noticing all these things and making connections I never did before. Or I’m appreciating different or enitrely new (to me) aspects of their character.

To quote Heraclitus: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.”

It’s kind of like that.

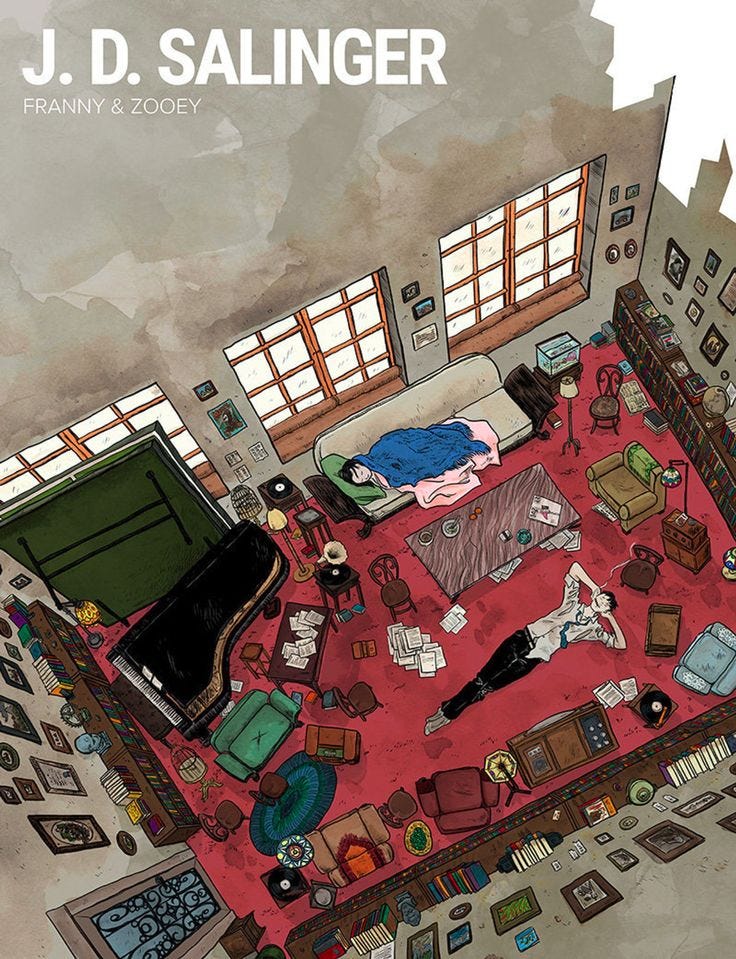

The last book this happened with was J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey—a superior book, as far as I’m concerned, to Catcher in the Rye (which I just re-read, too). It’s meant for adults, not adolescents, like Catcher is, and it’s about Salinger’s Glass Family, a large family of precocious but jaded metropolitans who were later the inspiration for Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums. The basic plot regards the sophisticated 20-something beauty Franny, a theater actor who experiences a nervous breakdown one weekend during the big game in an Ivy League college town. She finds her social circles and the people in it hollow and pretentious, inauthentic, playing a part to get attention and feed their egos.

Here’s the passage I underlined when I first read it in college:

“It's everybody, I mean. Everything everybody does is so — I don't know — not wrong, or even mean, or even stupid necessarily. But just so tiny and meaningless and — sad-making. And the worst part is, if you go bohemian or something crazy like that, you're conforming just as much only in a different way.”

True that.

This leads to a full-blown spiritual crisis (“I'm sick of not having the courage to be an absolute nobody,” she says at one point) and a retreat home to recover. Her mother Bessie and brother Zooey try to console her, but, in that unique way only a family member can get under your skin, only seem to make things worse.

A big part of the book—which I only recognized this read through—is how we tend to hide parts of ourselves, or not say what we really mean, to those we love the most, because they hold us accountable to a version of ourselves we at times would rather leave behind. Or we can’t quite receive love from a family member because they aren’t expressing it in the way we want, or they’re not perceiving this new part of us we really hope they will recognize and celebrate. Or we’re frustrated by them, because they still haven’t yet dealt with their shit, or their emotions surface in us some shit we’ve still haven’t dealt with ourselves.

Seventeen years separate the eldest and youngest of the seven Glass children and the book’s also about how inevitable it is that your family will fuck you up in some way, either by imposing their values and traditions upon you, or using you in some way to fill the needs of their own egos, or the difficulties in communicating across the chasms of generational divides. And as a result, you may get this impulse to escape into the arts, or ambition, or religion (Franny does all three). But, if we’re willing to forgive and accept the flaws and limitations of our parents, children, and siblings, we will discover a far superior sense of purpose and love, one that is practically divine.

Only after numerous failed attempts to overcome his own misanthropic nature is Zooey Glass able to deliver this exact message to his sister:

“I’ll tell you one thing, Franny. One thing I know. And don’t get upset. It isn’t anything bad. But if it’s the religious life you want, you ought to know right now that you’re missing out on every single goddam religious action that’s going on around this house. You don’t even have sense enough to drink when somebody brings you a cup of consecrated chicken soup, which is the only kind of chicken soup Bessie ever brings to anybody around this madhouse.”

Consecrated chicken soup, I love that. If you got some at home, drink up. That’s why I’m doing during this crazy period of life, anyway.