I Be Man Now, Please? #fortheboys

The plight of the young male author and our inability to receive masculine love.

So do we want, let alone need, more art and books by men? Or is it still down with the patriarchy, let other groups enjoy the spotlight instead?

Writers across Substack and publications like GQ and Esquire have been asking lately, wondering whether or not we care about finding and nurturing the next generation of young male novelists, who are conspicuously missing in action (I mean, can you name any male fiction writer under the age of 40?). Several noted that many men who in previous decades may have been novelists have instead turned to writing self-help or launching podcasts, which, as Andrew Boryga concludes in an excellent piece,

has less to do with men not having an interest in exploring themselves and their fellow man, or their relationships with women, on the page, but rather, men feeling like that exploration isn’t worth it because the result will often be ignored, panned, or rejected.

Without question, the status and desire for young male novelists has been devalued in America, perhaps even denigrated. There are various complex reasons why, some market related — men play more video games and barely read novels now, women make up 80% the customer base for new literary fiction — and some politically motivated — which I feel are too obvious to waste your time explaining. Of course, we still see novels written by men hit the bestseller list and win literary prizes, it’s just these men are all above the age of 40, and usually much older than that. And of course, a young male writer can still make a name for himself, can still garner large advances and earn celebrity status, but this predominantly occurs within non-fiction genres (business, history, self-help, etc.).

You may see none of this as a problem and I wouldn’t blame you. But I do wonder if it indicates a deeper issue in our society; mainly, if we’re capable of receiving and accepting masculine version of love anymore, let alone interested in its worth or appearance. And I do specifically mean a mature masculine version of love, not simply love that comes from someone who identifies as a man.

You might consider that a strange idea, there even being a masculine love and all. I mean, if I asked, could you describe what masculine love looks like? How it feels? Its unique benefits and advantages compared to a feminine love?

Hold that thought, as we transition to a far less controversial topic — the patriarchy!

Too often, I fear, we conflate masculinity with the patriarchy as synonymous entities. In a story I wrote years ago for VICE on “man camps,” I noted how the American Psychological Association (APA), in its first guidelines for conducting psychological practice with men and boys released in 2018, stated that traditional masculinity (defined as traits like “stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression”) was psychologically harmful and generally unattainable for men. In the Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, the brilliant feminist bell hooks notes, “Patriarchy demands of men that they become and remain emotional cripples. Since it is a system that denies men full access to their freedom of will, it is difficult for any man of any class to rebel against patriarchy.”

But like most feminists, her solution was that men should become feminists. Back in 2003 when she wrote the book, back when feminism was more associated with both genders having equal opportunity and access to independence, such an idea held merit. Unfortunately, this isn’t the message of feminism today, especially as it’s received by young men. In 2024, about half of young men believe they face gender-based discrimination (up from a third just five years ago), and more than half believe feminism has “gone too far.”

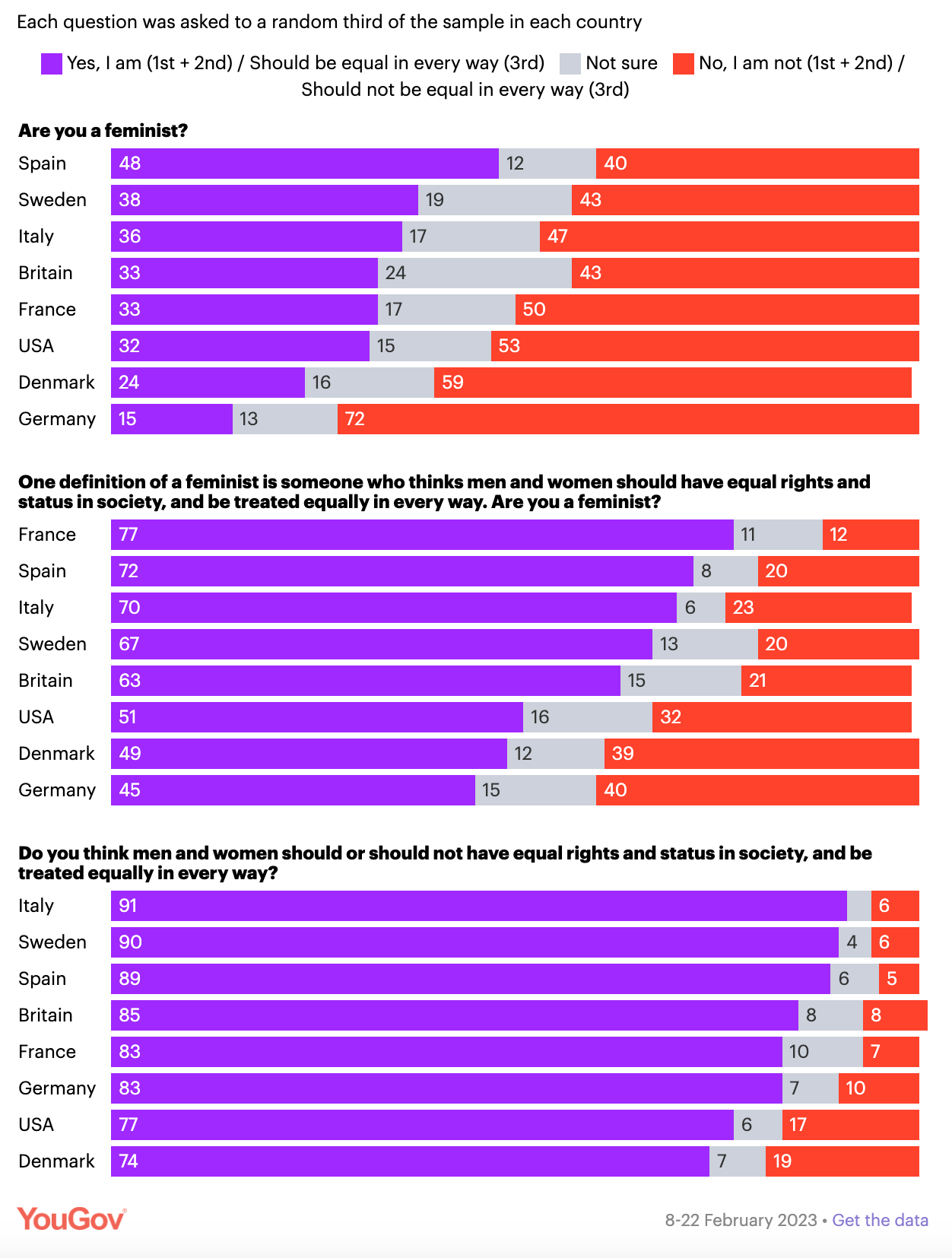

And before we place all the blame on America’s political extremism and culture wars, note how differently citizens across the West responded to the questions, “Are you a feminist?” vs. “Do you believe in the equality of both genders?”

It’s pretty stark!

Perhaps all this does is present men the opportunity to do what we should have done a long time ago—accept the responsibility to fix the problem ourselves. And to do so, I believe we must begin with a more useful definition of the patriarchy, courtesy of the Jungian psychologists Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette in their 1990 book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover:

In our view, patriarchy is not the expression of deep and rooted masculinity, for truly deep and rooted masculinity is not abusive. Patriarchy is the expression of the immature masculine. It is the expression of Boy psychology, and, in part, the shadow—or crazy—side of masculinity. It expressed the stunted masculine, fixated at immature levels.

The King, Warrior, Magician, and Lover in the title refer to what the authors identify as the four mature masculine archetypes. These correspond with the immature, boyhood archetypes of The Divine Child, The Hero, The Precocious Child, and The Oedipal Child. The authors note that “the adult man does not lose his boyishness and the archetypes that form boyhood’s foundation do not go away.” Instead, the mature man builds upon, rather than demolishes, his boyishness. A clear sign an adult man has reverted to a boyish sensibility (or in some cases, never grown out of one) is whether he accepts and takes responsibility in his business, relationships, health, and so on.

The Hero’s Journey is such a popular myth across cultures and history not because we need heroes to save us, but because it represents the journey all males must travel to break out of boyhood and achieve manhood. The Hero represents a boy’s ego at its most daring or powerful, believing he can be the one to beat the unbeatable foe and dream the impossible dream. It’s important a boy be allowed to think that, by the way, because sometimes he really does slay the dragon and save the world. But first the journey will throw the boy against his limits, showing him his natural abilities are not enough to win the day, and that he must learn to accept help from others, train past his comfort zone, and relinquish his boyish ego ideals.

You see this pretty clearly in a movie like Top Gun, where Tom Cruise as Maverick is a Grandstander, a Wonder Boy, too reckless and desperate to be seen as the hot shot hero, resulting in the rejection and disgust of his fellow pilots. Only when his actions cause the death of his navigator/friend Goose, and he loses the “Top Gun” title to Val Kilmer as Iceman (who signifies the mature Warrior archetype), does Maverick evolve, processing his grief and accepting he isn’t the best, doesn’t have to be the best. He moves beyond boyish fantasies and is able to accept his responsibilities as a man, which is what allows him to finally save the day in the film’s closing sequence.

On the flip side, I have no idea what the volleyball scene in that movie symbolizes, other than the glory of hot bods, homoeroticism, and aviators.

So there’s perhaps one important reason perhaps to nurture and publish young male authors—to share and update the wisdom of the Hero’s Journey in the language and context of our day. But, the authors write, “ours is not an age that wants heroes. Ours is an age of envy, in which laziness and self-involvement are the rule. Anyone who tries to shine, who dares to stand above the crowd, is dragged back down by his lackluster and self-appointed peers.”

They wrote these words, I remind you, back in 1990. Question: Do you think they are more or less true now than they were then?

I mean, just this week Ross Barkan wrote an essay in the New York Times titled “The Activist Left Doesn’t Want A Hero. But Does It Need One?” It’s a good read (Barkan also wrote a great Substack on the disappearance of young male novelists), but my main point here is that the absence of actual heroes worthy of our attention leaves a vacuum thats ends up getting filled with Prince Joffrey-like Boy Tyrants like Andrew Tate, Elon Musk, and Donald Trump.

So it’s here we return to this idea of masculine love, as expressed through the Lover archetype. We can go more into all the archetypes some later time, but for a mature man, the Lover archetype infuses a spirit of meaning and grace in his actions. He is sensitive and sensual, in tune with his feelings and what the Stoics called sympatheia, or the interconnectedness of all living things. He holds an aesthetic vision for the world, a way we can better appreciate and celebrate the beauty of nature and humanity.

In short, he is an artist. And it’s through his art that he connects with others and the world. He creates spaces for others to explore parts of themselves they otherwise couldn’t or don’t in daily life. I believe this sentiment was best captured by the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski, who held

a deep-rooted conviction that if there is anything worthwhile doing for the sake of culture, then it is touching on subject matters and situations which link people, and not those that divide people. There are too many things in the world which divide people, such as religion, politics, history, and nationalism. ... Feelings are what link people together, because the word ‘love’ has the same meaning for everybody. Or ‘fear,’ or ‘suffering.’ We all fear the same way and the same things. And we all love in the same way. That's why I tell about these things [in my films], because in all other things I immediately find division.

And if that’s what the next generation of young male authors is willing to offer us, then why are we ignoring, panning, and rejecting them? The answer isn’t so pleasant to consider.

Excellent, thoughtful read Brendan. I really appreciate how you weave data and sources into your work. Thank you, also, for the shout out.