Okay so let’s say you’re a writer who wants to pen stories, right, but you have this nagging problem stopping you—you’re broke. In fact, you’re dead broke. So you work a job to make money and squeeze in some writing in the few spare hours you can. Maybe with enough grit and determination, something will come from all that effort.

Sounds like a story you’ve heard before, right? Alright let’s add a few distinguishing details to our character then. Let’s say this character, who we’ll call Sean, is from the Marcy Projects in Brooklyn. He grows up in poverty and can’t even afford to buy a slice to satiate his rumbling belly. His uncle is shot dead when he is 9, which drives his father, his uncle’s brother, into inconsolable grief and heroin addiction. And this is so painful to Sean, causes him such suffering, he develops an allergy to his pockets being like bunny ears. He is gonna get to the top, he is gonna achieve the American Dream, and he is gonna do so with a vengeance.

“I’d rather die enormous than live dormant,” he writes.

Yes, even though getting the bag and making that skrilla claims most of Sean’s focus all the while he is writing. Each day he picks up his notebook and scribbles down all the ideas and lovely turns of phrase that pops into his head. Sometimes he loses hours on end doing this and organizes his stream of consciousness into verses. Did I mention Sean was a poet?

But wait, let’s add one final complication to Sean’s story. Let’s say he isn’t just good at making money—he’s exceptional at it. He has a CEO’s mind and an entrepreneurial spirit. He owns his own businesses, lucrative ones at that, and they take up more and more of his time. The luxury of jotting his thoughts on paper diminishes day by day.

What is Sean to do: Quit writing? Stay broke in the projects? Pray for a better tomorrow?

This, by the way, is the real story of Sean Carter, better known as Jay-Z, Jigga, Hov. He was a drug dealer who “really ran the streets,” with an operation that allegedly supplied crack cocaine to the Tri-State Area and stretched through every state along I-95. (Worth noting here: All rappers exaggerate their mythology; it would be disappointing if they didn’t.) And in that kind of profession, being someone always scurrying off to write rhymes isn’t always a good look. Nor is it all that practical to carry a notebook around.

So instead Jay-Z learns to hold onto those ideas and can store 4-5 complete songs in his head. He learns how to “write” multiple drafts in his mind and hone his verses sharp like a samurai blade. He likes having this little apartment in his brain that no one knows about or can access but that he can visit whenever he wants. Eventually, he ceases to put pen to paper whatsoever. By the time he reaches the studio to record a verse, it is so polished, full of such intricate rhyme patterns and double entendres, collaborators watch on in awe. It’s like Jay-Z is performing a magic trick before their eyes.

Bun B once told this story of having an in-depth conversation with Jay-Z and a couple others in the studio for 30-40 minutes when, all the sudden, Jay excuses himself to step into the recording booth and raps an immaculate verse. “He literally was writing a rhyme mentally in the middle of us having a conversation,” Bun said, “because some of the shit in the verse was literally what we were talking about.”

Writing this way had an odd effect on Jay-Z’s words—it simplified his message into something that was simple on the surface, easily received by the listener, but with a hidden depth for anyone who cared to look. He learned how to make money and earn respect at the same time. “I dumb down for my audience and double my dollars,” he once rapped. “They criticize me for it, yet they all yell ‘holla.’”

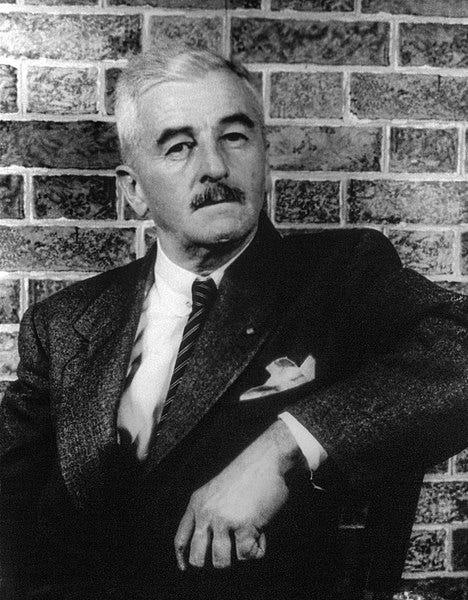

Funny enough, a writer who some consider the greatest writer of Southern literature employed a similar process—William Faulkner. “Pappy,” Faulkner’s stepson wrote, “really had no set routine. He worked in an apparently erratic manner. I do know one very important fact. He never carried a notebook or made any notes. He did not at any time carry a pencil or paper. He seemed to work largely from memory and observation.”

Faulkner noted that his stories often began with “a single idea or memory or mental picture” and he would play with that in his head until he understood what led up to that moment, or what followed. Until he knew that, he occupied himself by going for long hikes or hunting squirrels, physical activities full of silence that gave his mind freedom to explore and his body nourishment. Once the story was complete in his mind, his output was legendary: He composed As I Lay Dying in just 48 days by working in 4-hour concentrated increments in the middle of his 12-hour graveyard shifts at the University of Mississippi power plant. After such an outburst, he’d let his creative mind lay fallow, often waiting a couple months to write again.

Two writers from poor backgrounds stumble upon the same method for making art despite immense economic hurdles and industry outsider status. Perhaps most surprisingly, it led to radically different works—Jay-Z released platinum singles, Faulkner constructed literary labyrinths. But it’s a method that can work for anyone.

At least Faulkner thought so. During a University of Virginia writing class in 1957, he said he had “no patience” for any frustrated writer who blames his circumstances:

“I think if he’s demon-driven with something to be said, then he’s going to write it. He can blame the fact that he’s not turning out work on lots of things. I’ve heard people say, ‘Well, if I were not married and had children, I would be a writer.’ I’ve heard people say, ‘If I could just stop doing this, I would be a writer.’ I don’t believe that. I think if you’re going to write you’re going to write, and nothing will stop you.”