Tell me stories, but also, like, don't

Storytelling, Susan Sontag, The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms, John Berger, WWI, A Moveable Feast

As she so often did, Susan Sontag got straight to the heart of the matter with a sense of grace and elegance. In a 1983 interview, she was discussing storytelling with the critic and artist John Berger, who argued stories provide a kind of shelter for us to share lived experience and wisdom—the soldier who survived to tell the tale, ghost stories around campfire, parents telling bedtime stories to children. Yes, Sontag replied, though saying that was the primary function of stories seems more applicable in a society quite remote from ours. Today, she continued, “I’m always struck by the fact there is a kind of ambiguity in the very notion of storytelling.

“On the one hand we think of storytelling as a truth-telling activity. Tell me the ‘real’ story. We think of stories as bringing information. We think of stories as revealing secrets. True stories that might be told after someone’s death because the death of someone is generally an occasion for telling stories about a person’s life and some truth comes out that wasn’t discussed or generally shared before that person was gone.

“But we also think of stories as, That’s only a story. Or, Don’t tell me stories—meaning don’t tell me lies. And don’t you think at the very center of the whole enterprise of storytelling there is the fact that storytelling is an activity that faces in two directions. On one hand it’s connected with an idea of truth. On the other hand, it’s connected with an idea of invention, imagination, lies. One is thrilled by the story precisely because it describes something that can’t happen … it’s connected with fantasy.

“I think it’s all so, so complicated.”

I suspect a certain group of expat artists who traveled from Paris to the Basque hill country in 1925 to enjoy the Fiesta in Pamplona would agree with this notion of storytelling as a two-faced operation. As the humorist Donald Ogden Stewart, a member of that expat group, once said, “On the way back from Pamplona […] it occurred to me that the events of the past week might perhaps make interesting material for a novel. I was right. Ernest started work on the The Sun Also Rises the next week.”

Reading The Sun Also Rises for the first time is quite the revelation, if you open yourself to its magic. Unlike the books that came before it, which moreso followed that atavistic model Berger describes, Hemingway created a new kind of consciousness on the page that made the reader feel and experience the story almost as something that really happened in her own life. The writing is just so damn sensual and seductive. You taste the ice-cold rush of the wine Jake Barnes and Bill Gorton (who was based on Stewart) drink while trout fishing on a hot summer day. You hear the clacking and commotion of the bulls parading through town. You glimpse at all this hidden meaning at the words and off-hand gestures of the characters—those special moments in life, Hemingway noted, that most people aren’t conscious of but that “novelists build their whole structures on.”

It’s so revealing and gossipy that it makes you wonder, to borrow Sontag’s phrase, the real story behind the novel (as if such a thing exists). And there is whole cottage industry of tell-all memoirs that divulge what really happened that weekend in Pamplona. “They often point out the inaccuracies of Hemingway’s presentation of the trip,” as Frederic Svoboda writes in Hemingway & The Sun Also Rises, “and sometimes they portray the novel as a betrayal of confidences exchanged between trusted friends.”

Of course, if you know where to look, the novel paints Hemingway’s actions that vacation in the worst light of all, but that’s a different story for another day.

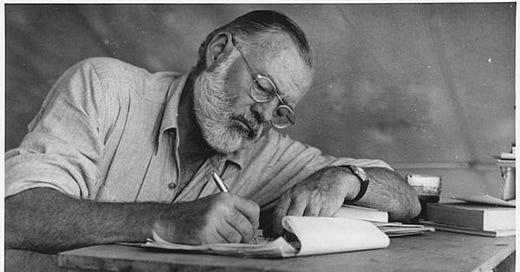

An early criticism of Hemingway, which you still sometimes hear, was that he was was a journalist playing at being a novel. He did not invent fiction, but instead was in the right place in the right time to report who, what, where, when, and why. But that people felt that way, in Hemingway’s mind, was proof of the success of his magic trick. “Imagination is the one thing beside honesty that a good writer must have,” Hemingway wrote in a 1935 Esquire article, “and the more he learns from experience, the more truly he can imagine. If he gets so he can imagine truly, enough people will think that the things he relates all really happened, that he is just reporting.”

That is the power of storytelling—you can make people believe fake and made-up things are true, are real. And in a way they are. A storyteller’s truth is an ecstatic truth, as Werner Herzog calls it, rather than a factual truth, an accountant’s truth. It’s an emotional, a spiritual truth, rather than a logical truth. But in Hemingway’s case, “to mistake his art for his biography,” Michael S. Reynolds writes in Hemingway’s First War, “is to mistake illusion for reality.”

Of course this is something we do all the time. That’s what Sontag was getting at with storytelling facing in two directions. The illusion of a great story can replace reality, superimpose its structures on our experience and memories. Stories give us perspective to see what we couldn’t previous. It’s why books and movies and art have been banned and destroyed since the dawn of civilization. It’s why the White House and Wall Street and Yellow Journalists work so hard “to control the narrative.” It’s why history is written by the winners and not the losers.

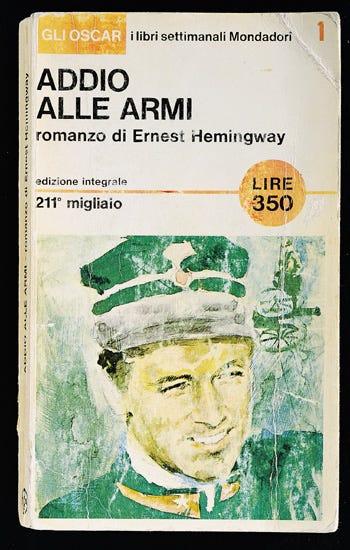

Besides its ending, the most famous moment in A Farewell to Arms is Frederic Henry’s retreat during the Battle of Caporetto. “For most people who have even a superficial knowledge of military history,” as one historian noted, the actions of the Italians in “Caporetto serve as the classical example of mass cowardice and military incompetence.” So embarrassing was Hemingway’s depiction that once Benito Mussolini came to power, the book was banned in Italy until after World War II. Mussolini couldn’t have his countrymen believe, not even for a second, that history might repeat and his fascist regime would fail and lead his country astray (of course this is exactly what happened).

But here’s the funny thing about all that—what Hemingway wrote in A Farewell to Arms was totally made up. A complete fabrication. Yes, he served in the Italian front in WWI, yes, he was wounded in battle, yes, he fell in love with his nurse, but during the months of Caportetto, he was already back in Kansas City working as a newspaper reporter. In fact, he had not seen the Tagliamente River or the surrounding terrain at any point in his life. Sure, he talked to some veterans who’d been there, read military histories, and drew on his comparable experience from the war. But at its core, what Hemingway wrote was only a story. Fiction, not fact, yet something more true than mere facts could ever be.

That’s the power of the pen. It’s why, as Hemingway wrote, “you can’t play with people’s attention. A good man who has the power of arresting attention at will must be especially careful.”

![Fiesta [The Sun Also Rises]. - Raptis Rare Books | Fine Rare and Antiquarian First Edition Books for Sale Fiesta [The Sun Also Rises]. - Raptis Rare Books | Fine Rare and Antiquarian First Edition Books for Sale](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Jefj!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faa01e4ad-3c55-4c22-9879-726194cee99f_1089x800.jpeg)