when a people business becomes a product business | on the death of Hollywood

Wes Anderson, Disney, art form vs. "real business," Netflix as "ponzi scheme," Scorsese...

A strange thing is happening at the movies. So strange that I paused several projects to write about this ... trend? movement? vibe shift? I’m not sure what to call it. All I know is that, whatever it is, I blame Wes Anderson for all this.

See last week I was feeling tired and uninspired. Austin, where I live, is doing its best impression of the fifth circle of hell and I needed some juice, some creative spark. For many years when that mood hit me, I’d go to the cinema. I still do ... just not as often. The movies themselves are to blame. As my friend Karan recently said, there’s like five good movies a year. Hyperbole? Sure. The international film scene is as vibrant as ever. But American cinema is in a sickly place. All these extended universes and IP-driven projects have slowly perverted the relationship between art and audience, transforming movies into something corporate, hollow, and boring.

But still I find reasons to go. Like Wes Anderson recently said, “Sitting in a cinema is better than sitting at home.”

And my curiosity was piqued when I read that Anderson’s latest film, Asteroid City, opened in six locations in June and set all sorts of specialty box office records. Best theater per average box office for a film since 2016’s La La Land, highest gross for a limited release film, and so on. Marketing and PR hype? Most definitely. But who knows, maybe the hype might actually lead somewhere this time?

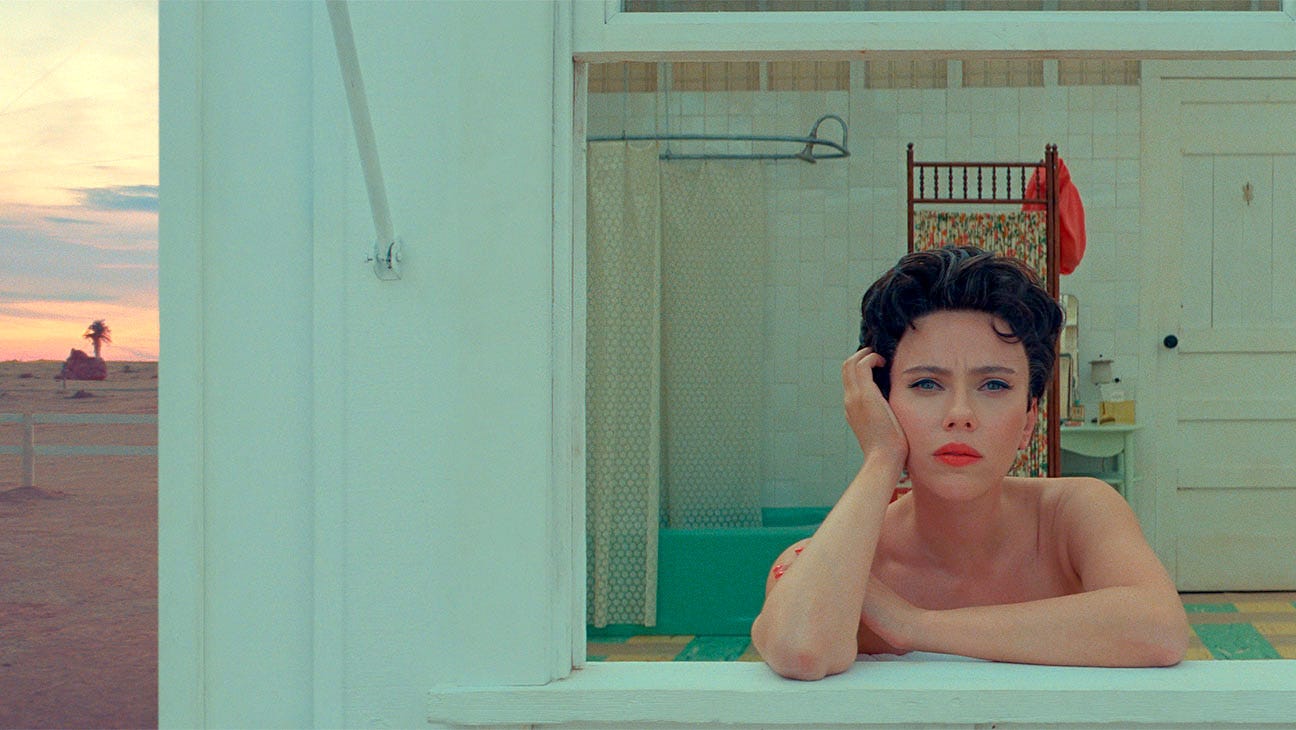

Within minutes of the opening credits I was transported in absolute glee. Here was a movie that reminded me why I loved movies. There was an original sense of style, place, and character, an artist who had something meaningful to say, and who desperately wanted to share that with all of us in that theater, which was totally packed.

It’s a movie very much about people — about our collective search for meaning in the universe, about what we as humans might offer one another, but also what vast distances we must be willing to travel, especially in adulthood, to meet others where they are. It’s probably the most Wes Anderson movie Wes Anderson has ever made, but the director confesses the purposes behind this aesthetic clearly and honestly — it’s a disguise, a mask, that hides the bleeding-heart, aching human-ness dying to be seen by others yet also terrified of how others can misunderstand and abuse us if we’re not careful. And yet still, we must try, even if the world might go on breaking our hearts.

I loved it. But as I drove home, a melancholy set in. It used to be that I’d see a movie that enraptured me every other week. But I hadn’t felt this way about a new movie in almost a year. Just how had film, which was once a truly American art form, the ultimate canvas for our country’s inner psyche, become so lost?

***

As Seth Godin said, “Our world is long on noise and short on meaningful connections.” Asteroid City is an attempt to cut through all the noise you currently find at the cinema. There are big, gigantic franchise movies, tiny independent films, and not much else. The middle, as we know, has dropped out and switched over to TV. In fact, the mediums have flipped roles in terms of cultural function. As Ben Fritz writes in The Big Picture:

Each Marvel “movie” is, arguably, best understood as a two-hour episode of an ongoing television show, while one season of Fargo or American Crime Story is, essentially, an eight or ten hour film.

But this change is something we all kind of accepted without really understanding why it was happening or for whose benefit. The shifting of the tides starts with Disney CEO Bob Iger. When Iger took over the company in 2006, he crunched the numbers and discovered that Walt Disney Studios profit margin in 2003 and 2004 was around 8 percent. For movie industry veterans, that was considered a "solid" return. For Iger, who came from the TV business where profit margins were closer to 20 percent, that was weak sauce.

For the better part of a century, a handful of hit movies covered the expenses of many losses for a film studio. Iger didn’t understand the strategy and labeled it “awful business.” What Iger discovered was that Hollywood lost most of its money on mid-budget movies like Asteroid City a.k.a. films with a ~$5-75 million budget aimed at American audiences. Blockbusters with a $100+ million budget, meanwhile, that prioritized simple plots and visual effects, were safer bets, because a movie could play overseas and capture massive returns in foreign markets, even if they failed with American audiences, almost like American audiences need not be the priority.

So Iger said play the hits, baby, and spent a decade remaking Hollywood in his image. He bought Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm for billions of dollars each, then spun off and sold Touchline and Miramax, studios in the Disney umbrella that specialized in mid-budget movies. Hello Iron Man and Luke Skywalker, bye-bye Dead Poets Society and Good Will Hunting.

From The Big Picture book:

Combined, the results were astronomical. Disney’s motion picture profit margin reached 21 percent in fiscal 2014, 24 percent in 2015, and 29 percent in 2016. Bob Iger was hailed on Wall Street as a hero. “The biggest change,” he told me in his typically blunt style, “is that people now look at movies like a real business.”

But it ain’t 2016 no more, is it? Iger stepped down as CEO in February 2020 and returned to the role last November after a couple disastrous years from his successor Bob Chapek. And it ain’t going so swell. Disney’s stock is down 55% since peaking in early 2021. Though Disney+ brought in $5.5 billion of revenue last quarter, the streaming service has $659 million operating loss. And the movies keep flopping, brother. Live action — Ant-Man, Thor, The Little Mermaid — and animation — Lightyear, Strange World, Elemental. One analysis states that over the past year Disney has lost $890 million at the box office. And that isn’t yet counting the new Indiana Jones movie, which all signs indicate will be a massive bomb.

Disney isn’t the only loser here. Warner Bros. will probably lose $350 million from the combined losses from Shazam 2 and The Flash and Universal will lose significant money from the recent Fast and Furious movie. At the same time, actors from these movies are lashing out. Anthony Hopkins described his role in the Thor movies as “pointless acting” while Elizabeth Olsen characterized her experience as Wanda Maximoff in the MCU as “very embarrassing.” All the director heavyweights too have come out against Marvel and franchise movies. Scorsese said these movies were not “cinema.” Tarantino labeled the actors who become famous from Marvel movies as “not movie stars. Captain America is the star. Or Thor is the star.” (Which made Chris Hemsworth super salty, by the way.) Veteran director Ken Loach called the movies boring, cynical, and made “as commodities like hamburgers.”

And here’s Godfather director Francis Ford Coppola on the matter:

When Martin Scorsese says that the Marvel pictures are not cinema, he’s right because we expect to learn something from cinema, we expect to gain something, some enlightenment, some knowledge, some inspiration. I don’t know that anyone gets anything out of seeing the same movie over and over again. Martin was kind when he said it’s not cinema. He didn’t say it’s despicable, which I just say it is.

Is this last stand from a dying breed? Or a sign that the workers are taking back their industry? It’s up for the audience to decide.

***

One business strategy taught early on at business school is the advantage of building a company with a great technology or system. A company that relies on skilled laborers operates at a disadvantage because those skilled laborers could a) leave the company at any time or b) leverage their necessity at the company to demand more pay and resources. But if you have a great technology or process, it doesn’t really matter who your employees are. Think of it as the difference between starting an artisanal sandwich shop with culinary chefs vs. creating Subway. One of those businesses can scale a lot faster, access a lot more customers, and make a lot more money.

If you want to understand what has happened in Hollywood over the past decade, I believe the answer lies here. Like most creative industries through the 20th century, Hollywood allowed a cultural mindset to drive its operations. There was a “right way” of doing things. That meant cultivating relationships with movie stars and auteurs, even if they released a dud or two. It also meant a perpetual hunt for “what was next.” What new star, new style, new director would capture the imaginations of audiences everywhere. Movies were a people business, not a product business. Now, the opposite is true.

We have discussed before that investing in art is not a linear model. This, I imagine, is what was so frustrating to someone like Bob Iger. He idolized the business model that Steve Jobs created with Apple, a company that develops several “killer” products every several years, then milks its customers to buy iterative versions of that product in perpetuity. You can see that he applied that model to movies and stories. The “killer” products were brands like Star Wars and Marvel, and the iterative versions are the different chapters within each brand’s Extended Universe. His belief was that in our era of Peak Content, this was how a business reached its customers. “When consumers are faced with so much choice, it’s very helpful to them to know going in what something might be,” he told TIME in 2018.

But we’re seeing several cracks in this model. Chiefly, that it lacks innovation. One advantage of Hollywood’s previous model with its measly 8 percent profit margin was that it nurtured innovative storytellers, allowing them to develop their craft and build a connection with an audience over time. Previously, even with a studio film, executives would lease some creative control over to the directors and allow them to put a personal stamp on the product. But Disney doesn’t do that. Instead, in a very corporate twist, Disney considers directors “brand managers” who are there to execute the company’s vision. Allegedly, longtime Marvel executive Victoria Alonso recently said Marvel’s directors: “They don’t direct the movies. We direct the movies.”

Another crack in the system is streaming. Because of the massive attention and stock valuation that Netflix received by vertically integrating its content onto a digital platform, other companies like Disney, Paramount, etc. followed suit.

The only problem? Streaming may be a terrible business model if you care about something silly like real-world profit. One anonymous TV showrunner called the streaming model the "world’s biggest Ponzi scheme." Before when a movie was released, it first had a theatrical run, where it could make money. Then, came DVD or physical media sales. Then, a movie could be licensed to a premium cable station like Showtime or an airline. Then, finally a movie could be sold to a regular cable network like AMC. If a movie was super successful, like Star Wars, you could even license toys and other branded products out of it.

Multiple revenue streams from one product = good, right?

But the economics of streaming don’t work that way. Streamers are selling you a monthly subscription to a technology platform. That’s it. That’s the entire revenue stream. Netflix doesn’t release its movies in theaters, nor does it release physical media. By nature, it devalues the individual product of a movie or TV show. If the medium is the message, the message of a streaming platform is that the specific content you’re watching doesn’t matter, what matters is that you’re watching. But if a fan really loves a specific movie, the streaming business model actually inhibits their ability to demonstrate that affection through their purchasing power. After all, you only need to buy one subscription.

Here’s how the director Steven Soderbergh explained it to Vulture:

The entire industry has moved from a world of Newtonian economics into a world of quantum economics, where two things that seem to be in opposition can be true at the same time: You can have a massive hit on your platform, but it’s not actually doing anything to increase your platform’s revenue. It’s absolutely conceivable that the streaming subscription model is the crypto of the entertainment business.

So let me get this straight.

Lack of innovation + dropping stock valuations + handcuffed revenue streams + significant industry unrest + product launches that lose hundreds of millions of dollars = “real business”?

I mean, really? That’s real business? Or is it an awful business?

***

All this reminds me of a speech Martin Scorsese gave during the 2020 Palm Springs International Film Festival.

Now, look, I know the business has changed and everything changes all the time, impermanence, that’s what it’s about. It’s wide open though now: you can watch everything anytime anywhere, and that puts a burden on you, the viewer. Not all changes are all for the good. If we’re not careful, we might be tilting the scales away from that creative viewing experience and away from movies as an art form. And we can’t lose sight that it is an art form."

While the art of course can’t survive without the business. I have to say, that in the end, the business can’t survive without the art, which is made by people with something to say.

I suppose that’s the burden of the modern viewer. You must decide, with your wallet, if you’d rather buy a digestible corporate product from a beloved brand or experience a potentially flawed and messy work of art from someone with something to say. Do you want the business to lead the art or the art to lead the business? Decide whenever you’re ready. Me? I’ll be at the movies.

Really enjoyed this piece. Indeed, the average person prefers the tried and true experiences.

This is so well written. Excellent analysis, well researched and sourced. Interesting. Fair. Many examples. Need more writing by Brendan Bures. Miss you! Mark Z.