Kids, Let's Go Crazy (But Like, Poetically)

On when the elevator tries to bring you down, but the elevator is society and social media

Sometimes I feel like social media is a prison from which there is no escape. That we’re all gonna be posting and consuming content online until the day we die. That even if you prioritize manifesting a dream in reality—say, starting a business, publishing a book, creating community—you basically have to first become a content creator and build a buzz online. That, for the most part, we explore more inside the internet than out in the real world. That the only way we know if something or someone is valuable is if everyone else cares about it first (it’s trending, has the most views, the stock price is high). That we’re so scared to be vulnerable, to really allow ourselves to be seen, to take real risk that results in hurt and loss, that we adjust how we feel on the inside to match what we’re told is true, real, or fair on the outside. That we too easily accept it is the way it is.

But other times I don’t know. Other times, I worry that I’m projecting, playing this zero-sum game between the internet and reality that doesn’t really exist. That strangers are far kinder, smarter, and good-natured than I ever give them credit. That the world is not on fire and we’re not hopeless. That our best days as a species remain ahead and not behind us. That what we lack is not the ability to create new realities, but “the social courage,” as Rollo May calls it, “to relate to human beings, the capacity to risk one’s self in the hope of achieving meaningful intimacy.” That any hope we have to get past this doomsday, nihilistic story we keep repeating about our world—which, if we’re being honest, is getting quite boring and exhausting—begins with someone finally telling a different story about who and what we are, and us actually being receptive to hearing it.

Lately, I’ve been getting into existential psychology (is it obvious?), which combines existentialist philosophy (Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Sartre, etc.) with traditional psychotherapy. Unlike psychiatry, it doesn’t view symptoms of anxiety, alienation, or depression as mental illnesses to be eradicated from the psyche, but more as these internal check-engine lights that your life and/or relationships lack meaning, purpose, and authenticity.

Jim Carrey, who’s been open about having episodes of depression for much of his life, has talked about this:

Depression is your body saying, Fuck you, I don’t want to be this character anymore. I don’t want to hold up this avatar that you’ve created in the world. It’s too much for me.

Instead, he says, we should think of the word depress as “deep rest”—as in, I need to take a long break from acting this way and reset who I think I am.

Existential psychology was popularized in the West following World War II, when the horrors of concentration camps, shattered civilizations, and the atomic bomb caused many to feel life was meaningless and fear the darkness hiding in man’s soul. Because what was the point of even trying if some other country’s leader could push a button and wipe out an entire city or decide your race didn’t deserve to live anymore? Viktor Frankl, most responsible for causing existential psychology’s spread, had survived as a prisoner of Nazi concentration camps and observed what separated those who made it out and those who didn’t was one thing and one thing only — having a ‘why.’ Suffering, he noted, ceased to be suffering the moment it finds meaning; we can endure any ‘how’ so long as we have a sufficient ‘why.’

As he writes in Man’s Search for Meaning, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl found those whose attitudes and beliefs were chosen for or given to them by an outside influence (family, religion, country, etc.), eventually broke down when confronted with the evil and suffering from the Nazis. Their ‘why’ wasn’t strong enough for them to endure. Only those who’d chosen ‘what it all means’ for themselves made it through.

These observations, along with Frankl’s later research as a neurologist and psychologist, led him to conclude that it’s our personal responsibility as humans to explore and decide what makes life worth living for ourselves each and every day. That’s why we have freedom of choice. And when we avoid this task, we either become victims to our circumstances or end up conforming to society’s expectations. The world chooses for us.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that around this time came that great bland innovation known as the American suburb. Conformity, after all, can be quite the comfort. Though disguised as a symbol of our postwar prosperity, the suburbs were really this slow drip toward national convention, where so many people were suddenly living such similar lives that you could almost swap your existence with your neighbor’s and you’d hardly notice the difference.

J.D. Salinger actually has a good bit about this in Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters:

The announcer had them on the subject of housing developments, and the little Burke girl said she hated houses that all look alike—meaning a long row of identical ‘development’ houses. Zooey said they were ‘nice.’ He said it would be very nice to come home and be in the wrong house. To eat dinner with the wrong people by mistake, sleep in the wrong bed by mistake, and kiss everybody goodbye in the morning thinking they were your family. He said he wished everybody in the world looked exactly alike. He said you’d keep thinking everybody you met was your wife or your mother or your father, and people would always be throwing their arms around each other wherever they went, and it would look ‘very nice.’

It’s also worth pointing out that Valium was invented around this time and marketed to housewives, the primary archetype of postwar conformity, as a “chill pill” to salve their newfound drudgery and anxiety. Of course no one (read: no man) asked why these women didn’t want to put on their housewife costumes and sit at home all day—disconnected from their families and communities, devalued and disenfranchised by society—with nothing to comfort them but cooking and cleaning and those new modern conveniences like the dishwasher, vacuum cleaner, and washing machine to help them do it (huh, wonder why they were so upset!). Valium, by the way, was the pharmaceutical industry’s first $100 million pill and the most prescribed drug in America from 1969 to 1982, thanks to the ingenious marketing of Arthur Sackler, who persuaded doctors the pill isn’t addictive (just kidding, it’s highly addictive!) and “promoted Valium for such a wide range of uses,” Patrick Radden Keefe writes in The New Yorker, “that, in 1965, a physician writing in the journal Psychosomatics asked, ‘When do we [not] use this drug?’” The answer is yes, you can imagine Sackler responding—after all, he once ran a campaign that “encouraged doctors to prescribe Valium to people with no psychiatric symptoms whatsoever.”

(Later, members of the Sackler family ‘refreshed’ this marketing playbook when pushing their family company’s newest drug OxyContin, which later caused the opioid crisis in this country. What a cool family!)

Anyway, I don’t know if you remember this, because we all seem to not want to talk about it, but like four years ago there was this global pandemic that temporarily ripped away control from our lives while also completely reshaping society and its institutional structures, most predominantly via the Great Online Migration. Post-pandemic we work, shop, and communicate online. We watch content online while scrolling other content online. We discuss politics and decide the fate of our country online. We stay in touch with family and friends through group chats, social media updates, and the memes we DM online. In 2021, nearly half of adults 18-29 said they were online “almost constantly,” and actually the more money you make, the younger and more educated you are, the more likely you are to spend all your time online.

I think therefore I am, Descartes said. But now, to be online is to be alive.

And we’re all happy about this, right? I mean, was this not the great dream of our youths, when the internet meant escape from self, escape from society, escape from all our pain and worry? Does this not spell the arrival of the future, the phasing out of the old and welcoming in of the new?

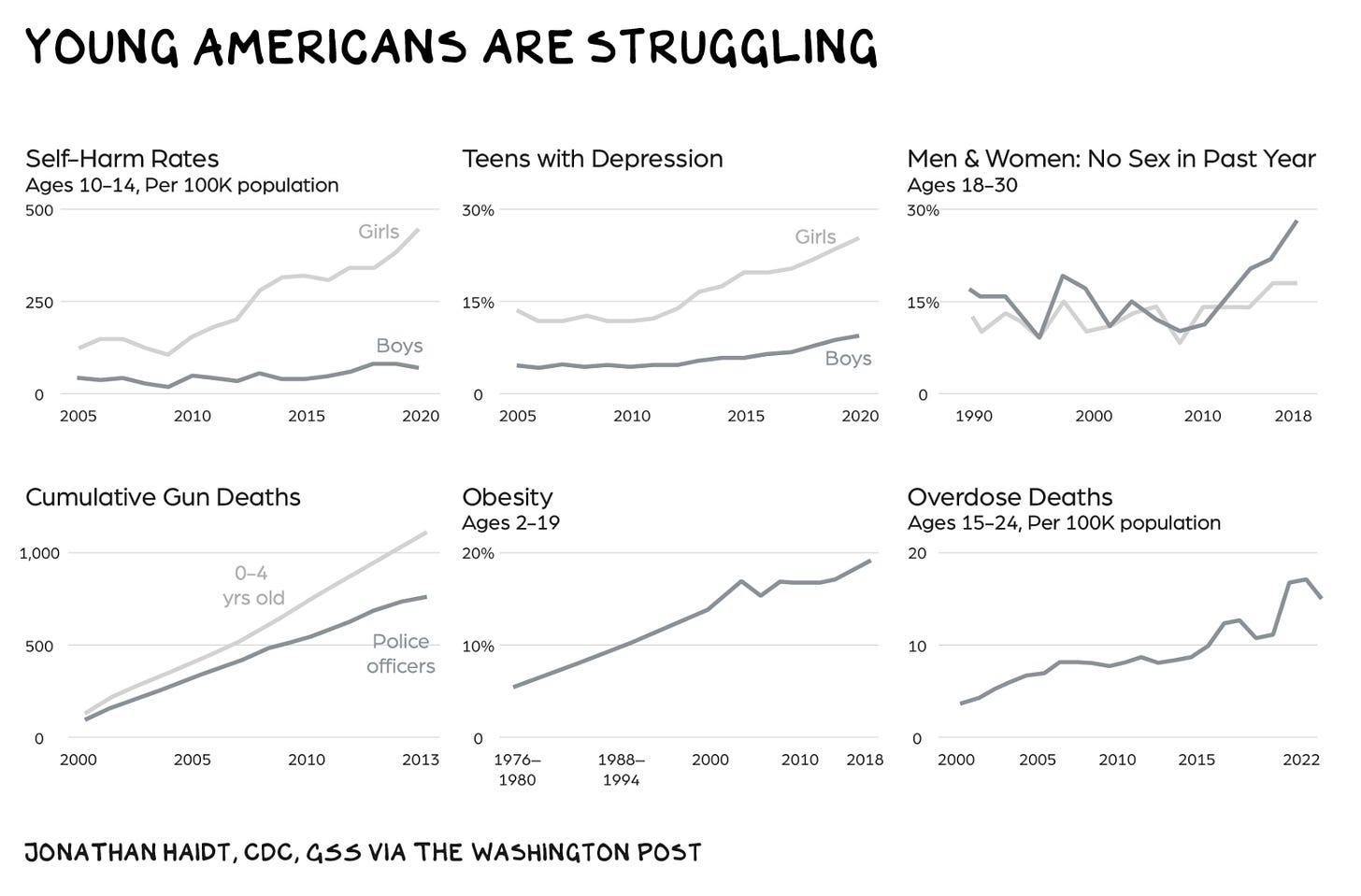

Well, actually the olds seem to be thriving while the youngs are all dying inside. Did you know the United States is the 10th happiest country in the world for people over the age of 60, but only the 62nd happiest for those under 30? A KFF study found that nearly half of adults ages 18-24 reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depression compared to just 20 percent of adults ages 65+. And monthly antidepressant prescriptions for Americans between ages 12 to 25 rose more than 66% between 2016 and 2022. “I feel like people are more anxious now because they don’t know what’s going to happen in the future,” said one patient in the KFF study, “because of the virus and the economy and everything else that’s going on...”

It would be convenient to blame all of this on our unresolved trauma around the pandemic, but “in the 10 years leading up to the pandemic,” an American Psychological Association report stated, “feelings of persistent sadness and hopelessness—as well as suicidal thoughts and behaviors—increased by about 40% among young people.”

Obviously, the proliferation of smartphones is a primary issue here, but so is the fact that 25-year-olds today make about $15-20,000 less than their parents and grandparents did while at the same time housing prices have doubled, child care costs have soared, and don’t forget all that student debt you have that previous generations didn’t either (the banks surely aren’t!). Exacerbating these problems is the fact that older generations have become hoarders of assets and resources. Those over 70 held 19% of household wealth in 1989 and now control 30%. Over that same time, household wealth for those under 40 fell from 12% to 7%. And why wouldn’t they hold onto that money? As any rich person will tell you, having capital to invest is what makes you money in America, not working hard—why else is real median income from labor up only 40% since 1974 while the S&P 500 has increased 4,000%?

Broke money ain’t make money, bro.

So without luck or help, a well-educated, young person almost can’t conform hard enough to get one of those bland suburban homes and “very nice” lives. It’s why Scott Galloway, an entrepreneur, investor, and professor, says the biggest problem in the United States isn’t “inequality, climate change, or war in the Middle East, but an issue that threads these threats together: America’s war on the young,” he writes (his post is where I got any unlinked statistics). It’s “a war of mutually assured destruction...We’ve broken the social contract that binds America: Work hard, play by the rules, and you’ll be better off than your parents were. For the first time in our nation’s history, this is no longer true.”

Ah, yes, just as our Founding Fathers envisioned—America, Land of the Rich and the Old, Home to the Young and the Exploited.

It’s enough to drive you a little crazy, really. But maybe that’s our problem. Maybe we’re not crazy enough, but like, crazy as in irrational, as in let’s stop playing by the rules and get a little weird with it, as in let’s quit trying to fix this broken, decrepit-ass system and dare to dream up a new one. You know, Joseph Campbell had this beautiful idea that the real power of myths and myth-making (and by that he meant making up your own myth) is that they helped you start to see your life as a poem, and yourself participating in that poem. You saw signs and symbols in your actions and adventures, and you trusted those signs and symbols were guiding you somewhere, even when, especially when, that somewhere didn’t make much sense in the moment. After all, life often doesn’t make much sense in the present—as Kierkegaard notes, “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards”—and so it requires real courage to believe in the meaning you create from within and follow a path in life that, with enough time and effort, becomes uniquely your own.

But all of that is a nuisance in a mechanized, industrial society that prioritizes efficiency and scale of production over the individual’s human experience of being alive. “Poets may be delightful creatures in the meadow or the garret, but they are menaces on the assembly line,” Rollo May writes. Because poets elevate and connect us to “creativity in art, poetry, music, and other areas that exist for our delight and the deepening and enlarging of meaning in our lives rather than for making money or for increasing technical power.” And it’s like, brother ew, who wants any of that? In this economy? In this election cycle? In these end times when we’re promised a new civil war and fresh apocalypse online every hour on the daily? (The Mayans ain’t got shit on mass media, boy.)

Nah, we can’t have any of that poetic nonsense in the richest, most powerful country to ever exist in the history of the world. Don’t be ridiculous now. And again, you can get depressed and anxious about all that or, as like me, you can take a page out of Roberto Bolaño’s book Distant Star: “In the current socio-political climate, he said to himself, committing suicide is absurd and redundant. Better to become an undercover poet.” I mean, they can’t exterminate us unless they find us, right? So whenever you see me on these dilapidated internet streets, I want you to know one simple and hard truth about me—I’m wearing a disguise.

I really appreciated reading 'Life lessons from Kierkegaard' (2013) last year. Happened across it randomly at Shakespeare and Company. It's concise and contains chapters with titles like “Why We Should Cultivate Dissatisfaction" and "On Not Thinking Too Much”. Available to read for free online at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifelessonsfromk0000ferg