why is it so hard to do my work? | the productivity paradox

On John McPhee, Medieval feudalism, technological determinism, Facebook, email, Cal Newport, Deep Work...

I want to tell you about a writer named John McPhee. And I want to tell you about him because he represents the paradox of productivity. You may know McPhee if you’re a nature and/or writing nerd like me. He’s a creative nonfiction vanguard and produces long, literary pieces on a variety of subjects — the Alaskan wilderness, cross-country truck drivers, the basketball pioneer Bill Bradley. He once wrote an entire book on oranges. Eclectic dude.

But the word most articles use to describe McPhee is “prolific” — this month, at 92 years old, he published his 34th book (most of his books, by the way, are bangers). That is in addition to his 50-plus-year career as a New Yorker writer producing longform magazine articles, while also being an influential teacher at Princeton University and an avid fly fisherman. So avid, in fact, he keeps a journal that details every catch he’s made, how many hours he spent fishing each day, the river’s temperature and current, plus a category called “AWOLs” — the ones that got away. Oh, and every other day, he rides his bicycle 15 miles. Productivity legend, right?

But McPhee does not view himself that way. He admits to often struggling to write even 500 words a day, spending all day staring at the wall, before 5 or 6 in the afternoon, when worry strikes that he might waste the day and he’s able to squeeze out some writing. Early in his career, while on assignment for the New Yorker, he once laid down on the picnic table behind his house for two weeks straight and stared up at the branches of an ash tree “fighting fear and panic, because I had no idea where or how to begin” the story. “The piece would ultimately consist of some five thousand sentences, but for those two weeks I couldn’t write even one,” he wrote.

“People say to me, ‘Oh, you’re so prolific’ … God, it doesn’t feel like it — nothing like it,” McPhee said. “But, you know, you put an ounce in a bucket each day, you get a quart.”

McPhee works slow and old-school. He may report and research a story for eight months before writing and has never used a traditional word processor in his life. Instead he is one of the world’s last users of a 1980s program called Kedit to organize and produce his writing. (Don’t try and use it yourself, by the way — the program essentially shuttered in 2007.) In the preface to Annals of the Former World, his Pulitzer-winning geologic history tome, he describes writing as “masochistic, mind-fracturing self-enslaved labor.”

Read about his writing process and you may understand why. From a 2017 New York Times profile:

[His] process is hellacious. McPhee gathers every single scrap of reporting on a given project — every interview, description, stray thought and research tidbit — and types all of it into his computer. He studies that data and comes up with organizing categories: themes, set pieces, characters and so on. Each category is assigned a code. To find the structure of a piece, McPhee makes an index card for each of his codes, sets them on a large table and arranges and rearranges the cards until the sequence seems right. Then he works back through his mass of assembled data, labeling each piece with the relevant code. On the computer, a program called “Structur” arranges these scraps into organized batches, and McPhee then works sequentially, batch by batch, converting all of it into prose.

Before he had a computer, “McPhee would manually type out his notes, photocopy them, cut up everything with scissors, and sort it all into coded envelopes.” His first computer, he once joked, was just “a five-thousand-dollar pair of scissors.”

Insane, right? In an age of AI-generated audio transcription and organizing software like Evernote and Scrivener, in a time where we possess more productivity tools than ever, why continue to work this way? Why not get more done faster? Perhaps, because the relationship between technology and productivity is not as linear as we thought.

***

Among technological historians and academics lies a strange fascination with Charles Martel (grandfather to Charlemagne the Great) and the rise of the Carolingian dynasty, which instigated feudalism in medieval Europe. For a long while the story went that after a narrow victory against the Moorish cavalry, Martel realized the tactical advantage of horses deployed in war, and so seized church lands to establish horse farming and installed vassals on them. All the other lords got jealous — you mean, you can just steal church lands; I want some! — copied Martel, and that’s how we got feudalism, baby.

But in the 1950s, historians discovered the dates were wrong. Martel seized church lands to establish horse farming a year before that pivotal battle with the Moors. So what prompted Martel to steal the lands, turn to horse farming, and accidentally create Medieval feudalism? The invention of horse stirrups, according to excavation records uncovered by historian Lynn White, Jr. Because with stirrups, a rider could thrust the full momentum and might of a horse into a lance blow, a devastating attack previously unforeseen in European military tactics. “Without them,” writes mechanical engineering historian John H. Lienhard, “[soldiers] couldn’t fight on horseback. Swing a sword, or run a lance, and you fall off your horse. You could get into position quickly on a horse. But then, unless you were crazy, you got off and fought on foot.”

It was a revelation to Martel, who wanted this new power all for himself and his army. Thus, stealing church lands and horse farming and vassals and so on. Although stirrups as a technology had simple origins — to make horse riding easier — they had mighty unintended consequences — the rise of medieval feudalism. Lynn’s narrative forced historians to admit “they’d been looking in the wrong place ... Kings and queens don’t shape the world,” writes Lienhard. “Artisans, millwrights, and engineers do.”

As a result, late 20th century academics and historians searched to connect other instances in which tools altered our behavior in ways that weren’t intended or predicted by inventors. These narratives lead to a new theory called technological determinism, which posits that a society’s technology can determine its cultural values, social structures, and history. It’s a bit spooky — the machines control us, bro! — and perhaps too reductionist to understand the whole of human history. But I think it’s hard to refute that technologies can have unintended structural consequences for society.

For a more modern example, we have Facebook’s Like Button. You may not remember Facebook once didn’t have a Like Button. Engineers created it in 2009 after noticing many comments below posts and photos were simple, positive exclamations like “cool” or “nice.” To remove clutter, create a cleaner aesthetic, and prioritize more substantive comments (lol), engineers offered users the “Like.” But the “Like” had an odd, unpredicted side effect — users suddenly spent way more time on Facebook. People logged in multiple times a day to check how many likes, i.e. how much approval, their posts and photos received. Every other social media company soon followed suit and incited the modern attention economy. On average, people now check their phones about 150 times per day and more than half of Americans admit to being addicted to their phones.

***

But before Facebook, Uber, TikTok, etc., email was the darling tool of the business world. “In my mind, there is no doubt: electronic mail is the killer app for the 1990s,” wrote Peter Lewis in a 1994 article. There were doubters, too. “E-mail is fun, but it’s a toy,” said one story analyst at Columbia Pictures in 1992. “E-mail encourages people to chatter and say things that don’t need to be said,” he added.

Email is one of those productivity tools we assume is good, due to its longevity. But as Cal Newport argues in A World Without Email (where those quotes and others in this post come from), our relationship with email was something we stumbled into, rather than chose, and represents another example of technological determinism.

He offers what happened at IBM headquarters when the company installed its first internal email system as a case study. Before email, communication at big corporations was a pain. Employees would leave post-it notes on cubicles, play phone tag, and wander the offices to contact the person they needed to execute a work task. This tedious back-and-forth could go on for days. “An important reminder that the world before email was no prelapsarian paradise,” Newport writes. IBM assumed email would simply replace all this analog communication and assigned a young employee named Adrian Stone to quantify the volume of communication already occurring in the office. Then, they would buy a mainframe to handle that existing communication load.

Once Stone determined an estimate for the server needs …

The system was configured and deployed, and once activated, it was a hit among employees; too much of a hit, as it turned out. Within a few days, they “blew” the server due to overload. As Stone told me, they experienced five to six times more traffic (Newport’s emphasis) than he had estimated, meaning that almost immediately after email was introduced at IBM, the volume of internal communication exploded.

A closer examination revealed that not only did people send many more messages than they did in the pre-email era; they also began cc’ing these messages to many more people.

Problems that were once solved quickly with a real conversation between two people suddenly become bureaucratic and bloated. A decision now unfolded over numerous threads, drudgingly pinging back and forth, with too many cooks in the kitchen. “Thus — in a mere week or so — was gained and blown the potential productivity gain of email,” Stone joked.

The average white-collar worker in marketing, advertising, finance, and media now spends up to 60% of the workweek engaged in electronic communication. In an internal survey, Microsoft found that meetings and emails took up so much of the workday, employees were logging on between 9-11 p.m. to get their actual non-email, non-meeting work done. A 2018 survey of 50,000 workers found that on average employees were checking communication channels like Slack and email once every six minutes. The opening chapter of Newport’s book is basically people venting about how much anxiety and stress their email inbox gives them, frustrated they can’t work any other way.

All this nonstop chatter has created what Newport calls the Hyperactive Hive Mind: an unstructured and asynchronous workflow that relies on employees always being “on” and constantly switching tasks in response to the latest message received. The problem is our caveman minds aren’t particularly equipped to work this way. In a 2009 study called “Why is it so hard to do my work?,” researcher Sophie Leroy found the human brain literally can’t multitask. When you switch from one task to the next, even if you just check your email real quick, the first task remains on your mind for some time — a measure Leroy called attention residue — and your performance of the second task suffers as a result. Stacking multiple task shifts up over a day causes what I experience as “fuzzy brain” — an overwhelmed state of mind where my brain’s electrical circuits go haywire and I need to lay down and not look at screens or talk to anyone. Indeed, those who multitask and constantly context shift, are shown to have poorer memory, struggle to filter out irrelevancy, and are more easily distracted.

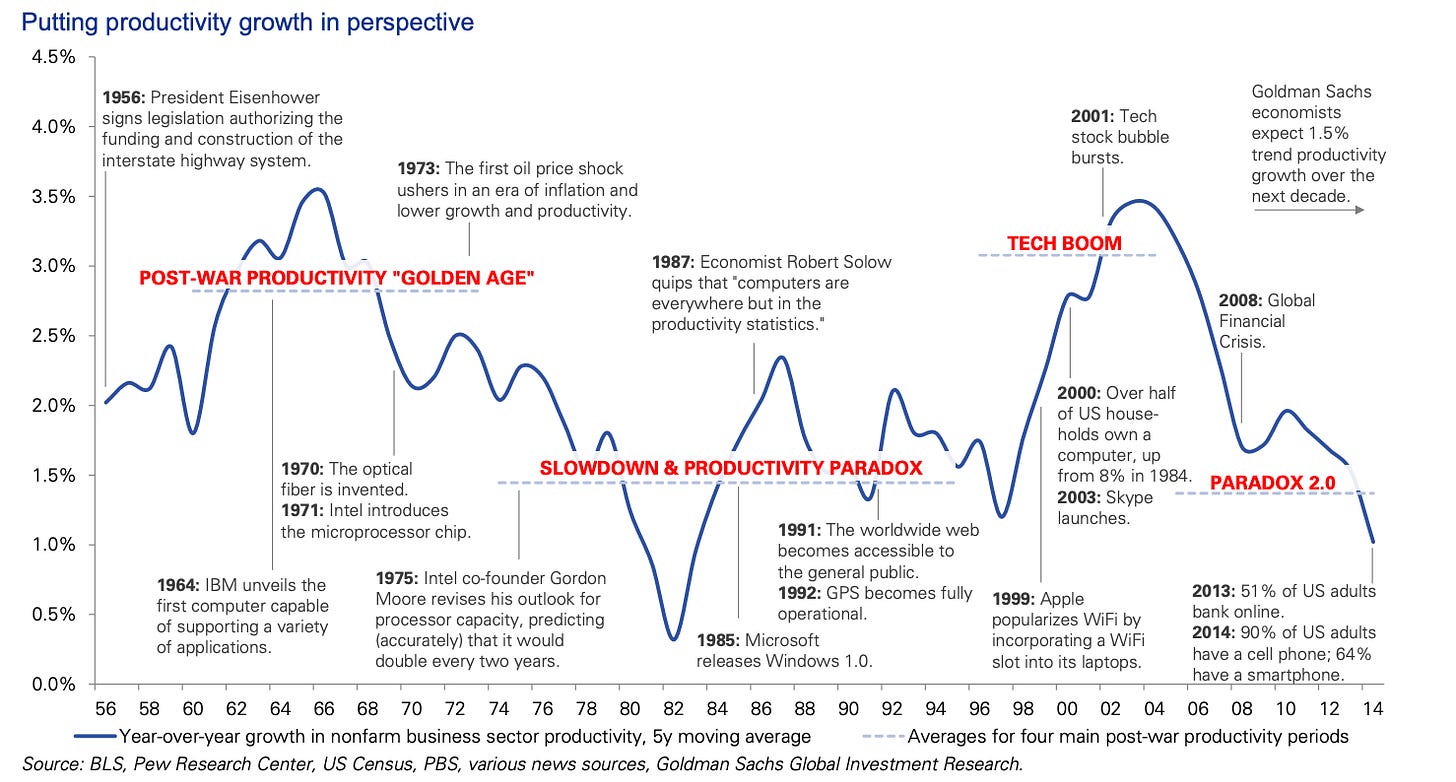

And so despite grand technological advances to create more efficient workflows, workers have been getting less productive work done per hour of work for the past 20 years. This tension between technology and productivity, first observed in the 1980s with the rise of computers, is what economists call the Productivity Paradox — technology may allow workers to complete tasks faster and with less effort, but that same technology leads to more distraction and procrastination and less output.

So if you feel you get nothing done at work, don’t worry. You’re just part of the trend.

***

All of which brings us back to John McPhee. Stubbornly, the man has not allowed new technology to change his process, once quipping that for him the future stopped in 1984. He prioritizes what Newport coins as Deep Work, i.e. professional activities performed in a distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive abilities to their limit, creating new value and improving your skill. Deep Work can be hard and painful. Most of us recognize that moment of staring down a tedious pile of paperwork or a massive difficult problem in a project. New technology, if we’re not careful, allows us to run away or engage in Shallow Work like emails, seeming like we’re moving the ball forward to co-workers and managers, while nothing important gets done.

This is not a generational problem. Research suggests Baby Boomers and Gen Xers consider their phones to be a necessity more than Gen Zers and millennials. If you’ve ever had an email-obsessed boomer boss, who can’t help sending notes at midnight, you know what I’m talking about.

And remember that 92-year-old McPhee called writing “masochistic, mind-fracturing self-enslaved labor.” Great work often includes hard and annoying parts to it. But for McPhee, his hellacious process of collecting and organizing data unlocked his ability to do the work he really wanted to do. “The procedure eliminated nearly all distraction and concentrated only the material I had to deal with in a given day or week,” he writes. “It painted me into a corner, yes, but in doing so it freed me to write.”

For McPhee, technology unlocks his process to write because it creates structure and boundaries for him to explore and bounce up against. This is what he was doing back in the 1960s for two weeks staring at the tree branches — determining the structure of his story. It seemed like he was doing nothing, while in fact, he was doing the most necessary work imaginable to proceed. Because without structure, stories can “spaghetti,” i.e. sentences go all over the place with no discernment or intention, and leave the reader confused and bored.

“A piece of writing has to start somewhere, go somewhere, and sit down when it gets there,” McPhee writes in Draft No. 4, his book on writing. “You do that by building what you hope is an unarguable structure. Beginning, middle, end.”

Now, he creates odd little structure diagrams as the roadmap to guide all his stories. Here’s one he made for his story “Travels in Georgia,” a profile of Georgia biologist-ecologist Carol Ruckdeschel.

The lesson: True productivity is much slower than we wish. Probably, it should not be measured in what we accomplish in a day, but in larger time blocks, like a quarter or a year.

A final note here. McPhee did not set up his writing program Kedit and all its macros and widgets. He had help from a man named Howard J. Strauss, who previously worked for NASA before landing in Princeton’s IT department. McPhee once joked that Howard’s contribution to his use of the computer was so extensive that if Howard “were ever to leave Princeton I would pack up and follow him, even to Australia.”

Howard, who died in 2005, was the polar opposite of Bill Gates — in outlook as well as income. Howard thought the computer should be adapted to the individual and not the other way around. One size fits one. The programs he wrote for me were molded like clay to my requirements — an appealing approach to anything called an editor.

You may or may not have a Howard in your life. I know I am lucky to have several. But the point is essential: A technology should be molded to fit its user, not the other way around. It’s unlikely major tech companies will ever do that for us. So it’s important we take the time, or seek out the help, to do that for ourselves, even if it feels like we’re laying on a picnic table doing nothing for two weeks. Because when we do, we’ll have the structure we need to finally get our work done.

I thought this was an interesting article. I have felt the same way many many times in my life. I have always felt that doing things "the old school way" was the best way for me to wrap my mind around things and then go at them authentically. I also feel that with modern technology and social media, we are not being pulled in ten different directions, rather we are voluntarily giving ourselves up as a tribute to be sent out in one hundred different directions at one time. We try to do so many things that we often fail to invest time and energy into doing one thing well.

Great article. I am trying to become a better writer and I was hoping I could ask you, Brendan, if you recommend Paul Wix's course for someone who has no history of writing professionally. Someone who loves writing and is just trying to find a way to write better and more authentically. Thanks!