To the Old Gods and the New

Art vs. commerce, the mythology of self, the responsibility of artists, and parasocial influencers

The war may not be lost, I thought the other day. What war? you ask. Put simply, the battle for your eyeballs in the attention economy. But I hate that term, “attention economy.” It's a dumb, blunt buzzword for something, I believe, that is much simpler and more eternal.

That something would be the war between art and commerce. You used to hear about the war a lot, especially in creative and academic spaces, but not anymore. We're all making content and shooting visuals now, baby. No one even criticizes artists for selling out anymore. Instead, we're excited so-and-so blew up and “got the bag,” an acceptance that in a globalized capitalist system, money is the most desired form of power that exists.

It reminds me of this essay The Roots drummers Questlove wrote about how hip hop failed Black America. I always remember these lines he wrote about Lorde (how odd that Quest has thoughts he wants to share about Lorde, I remember thinking) and how the chorus of “Royals” skewers and:

... critiques one version of hip-hop’s values, Cristal and Maybachs and gold teeth, and while it’s reductive in some ways, it’s also instructive, because it shows how the signifiers of hip-hop culture (which has swallowed black culture in general) have lost much of their cool. They’ve emptied themselves out and don’t know how to fill back up. The criticism that Lorde’s references are four or five years old, at least, does nothing to dull her point and may even sharpen it, because even if the names of the products have changed, their meaning(lessness) remains the same.

He wrote that nine years ago. Not much has changed since then. If anything, hip hop, and much of popular music in general, celebrates opulence, and the dogged pursuit of it, even more than it did then. Commerce won.

But I suspect art may be staging a comeback. Something is in the air. The first step, if the comeback is to be successful, is redefining what art is and what art isn't. Or rather, for us to remember what art always has been, which is the mere act of creating something that did not exist before, that hasn't existed before, at least in this unique way, and putting it out into the universe. Art is everywhere when seen through this kind of lens. Having a deep conversation with a friend is a type of art. Cooking dinner with the random ingredients in your fridge, and it actually tasting good, is art, too. Even those hallmarks of capitalism like starting a business or creating a marketing plan can be art in the right hands.

As Rick Rubin writes in The Creative Act, what you make “doesn't have to be witnessed, recorded, sold, or encased in glass for it to be work of art. Through the ordinary state of being, we're already creators in the most profound way, creating our experience of reality and composing the world we perceive.”

There's this lovely quote I discovered while reading Olivia Laing's The Lonely City. In his journals, the artist David Wojnarowicz once wrote:

I WANT TO CREATE A MYTH THAT I CAN ONE DAY BECOME.

I love this line so much1: the possibility found within change and reinvention, the hint at what power is only possible through mythology, and the personal responsibility of actualizing your potential. It is just so damn hopeful, brimming with desire and the will to be better and something more important. Most of all, it is a declaration of war against the ego, which wants to control reality, keep it and your identity within that reality fixed and at the center of the universe.

Instead of being the center of the universe, it asserts that you are a creator within the universe, just as Rubin noted.

Over the past year, this thesis has developed in my brain about art and power. Basically, I've wondered why so much of contemporary art, thought not all of it, strikes me as meek, weak, or placid. The force of vision in writers like Roberto Bolaño, Sylvia Plath, or Ernest Hemingway or in films like Seven Samurai, Taxi Driver, or even something like Star Wars or Indiana Jones. These 20th century works explode outward, expanding the world as we know it, whereas work in this century tends to gaze inward, reducing reality to a more manageable size2.

Anyway, my thesis is twofold:

1) Mythology, or a sense of the mythic, is what grants art much of its power

2) The social interent, where postmodern poses flourish, actively destroys a mythic sense of the world

Myth, as the OG Joseph Campbell notes, is a mirror for the Self. The Self here is the Jungian Self, which is something like the Soul.

It is the Self you're looking for when you ask, “Who am I?” It's a fascinating question, because, as Alan Watts once noted:

...it’s so mysterious; it’s so elusive. Because what you are, in your inmost being, escapes your examination in rather the same way that you can’t look directly into your own eyes without using a mirror, you can’t bite your own teeth, you can’t taste your own tongue, and you can’t touch the tip of this finger with the tip of this finger. And that’s why there’s always an element of profound mystery in the problem of who we are.

Sometimes who you think you are is not who you are. Or sometimes who you are is not who you want to be. That is another fascinating question: "Who do I want to be?" There's an entire cottage industry of speakers and YouTube videos and social media coaches dedicated to helping people find that answer. But the best solution many have is either find a better job or become an entrepreneur, as if the production of labor is the only mechanism to produce a meaningful life. It's one way, sure, but not the only way. American culture has mostly abandoned religion and literature and art as frameworks to find meaning in life. In essence, we have abandoned myth as a utility to understand who we are and what we're doing here.

But you are here for reasons besides making money.

Being alive is confusing and strange. The more I learn, the less I understand. In various ways, to be human is to live in paradox. We are intelligent beings driven by animal impulses. We seek both social communities and individual glory, i.e. we want the sole power to shape the world around us, but it means nothing without significant relationships. Speaking of which, our genes guide us to both mate in pair bonds and to seek extracurricular affairs outside that pair bond. (As Alexandre Dumas once wrote, “The bonds of wedlock are so heavy that it takes two to carry them, sometimes three.”)

How does an artist pierce through this mess? How might she connect with an audience who is dealing with all the existential wonder, awe, and horror of being human?

For like a 100 years in music, the answer was the single. In the early 1900s, musicians released singles since that was the maximum amount of storage the technology — shout out gramophones, baby — would allow. Then, the nerds figured out how to compress those chunky boys down to a vinyl format and fit a ton more songs on there, birthing the Long Play, the LP, the music album. For a long time, music did not exist without the musicians present, but the single became a technology for music to fill spaces where the artist is not present.

Obvious perhaps, until you ask which spaces should the music fill? Beethoven and Mozart wrote music for packed, cathedral-like music halls, and so composed epic, giant symphonies to fill that space. But 20th century pop musicians had to fill many different spaces: your car, your living room, the dance club, a football stadium. For a single to spread and grow, an artist was incentivized for the music to sound good in as many spaces and as many aspects of your life as possible.

Fortunately, artists like The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Nina Simone had an advantage Beethoven and Mozart did not. They had words and these words could tell a story, they could create symbols, they could birth characters. In other words, they weren't only musicians and composers anymore. They were poets, too.

And so these artists did what poets have always done through words. They reached for the universal, the mythic: various emotions, ideas, and patterns of human experience that have held true backwards and forwards through the years. It wasn't an exact facsimile of your identity and experience, but a "patterned mirror," as Campbell likes to call it, where you could glimpse some eternal truth or wisdom that helped you understand what you're going through in life and how you might get through it. "Myth lets you know where you are," Campbell says.

To enter any mythological framework — religion, story, art — you need to leave part of your individuality at the door. Myth reminds us how we're not that different after all. The single was a bridge to the artist and their work, yes, but it was also a bridge to each other. It was a parasocial relationship before the media coined the term. You had to make your ego smaller so everyone could fit within the framework and artists had to create a framework big enough for everyone to fit.

Social media, on the other hand, acts in an opposite matter, for those not careful. An algorithm is designed to show you the world how you want to see it. It emphasizes, at all turns, how different you are from your neighbors. They like vanilla ice cream and you like chocolate. You're not racist, after all, unlike those vanilla bean-eating cracker mother fuckers.

Gone is the burden to appeal to a universal sensibility. You can appeal to your specific niche audience and make tons of money. There are influencers you or I have never heard of who have dumby followers and dumbier amounts of money. There is little incentive to give a shit about other people. It's strategic, in fact, to piss off those who are not your followers and sow the seeds of division. Donald Trump won a presidential election by becoming the best online troll to ever exist.

Yet so many money-making influencers end up depressed, anxious, or suicidal.

One study found that for women ages 18-35 there was a positive correlation between time spent on Instagram and "a range of psychological wellbeing outcomes, including depressive symptoms, general anxiety, physical appearance anxiety, self-esteem, and body image disturbance." There was a similar correlation, interestingly, with the amount of followers one had. The more followers, the worse their mental health. This corresponds with another study about Facebook from 2012 (!!) "that those who used Facebook for longer, and who followed more strangers, agreed more that others had better lives."

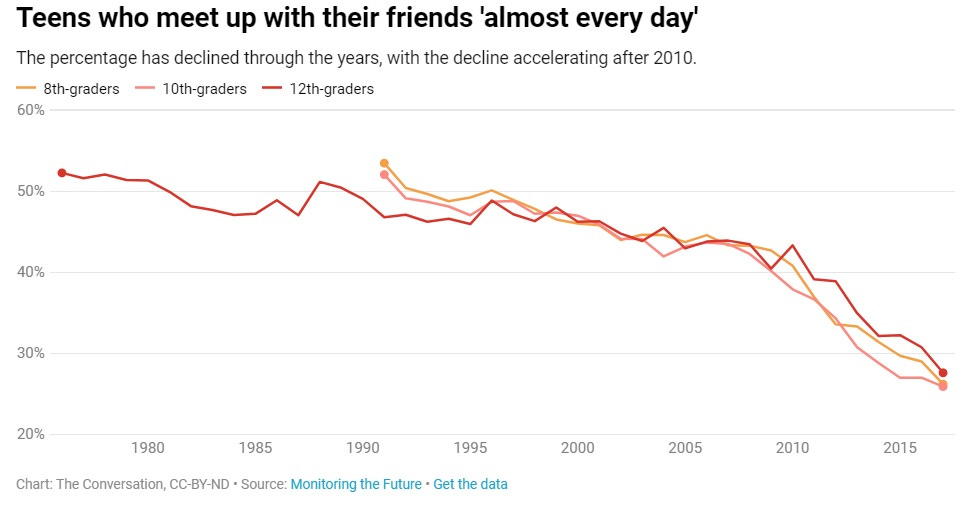

The teens, in general, don't seem alright. It seems like all of them feel very alone. Since 2012-13 — when U.S. households crossed the 50% threshold for smartphone and social media — they're all hurting themselves more, liking themselves less, and spending more time alone. This is especially true for young women.

The data is not good here, Bob.

One myth about the internet is that it would connect lonely introverts who couldn’t find social bonds, or people they like, in real life. It's a good reminder that some myths must, in fact, die out. It allows new myths to rise from the ashes.

Wojnarowicz was successful in becoming a myth, by the way, and was a powerful activist for gay rights and the AIDS crisis. Activist-artists today could learn a lot from him. Here's a good deep dive.

Writers like Ottessa Moshfegh and George Saunders or directors like Jordan Peele and Bong Joon-ho are top-of-mind examples of the exception to this idea.

I really loved this article. I was thinking about some of the data points you brought up the other day but in the context of people reading and its possible effects on and connections to phenomena like loneliness or lack of empathy.

I also am in agreement with the need for art to create more mythology for people to find themselves in. Star Wars is a great example and I am elated that you used it. I am a teacher and find myself often thinking about Harry Potter in this way.